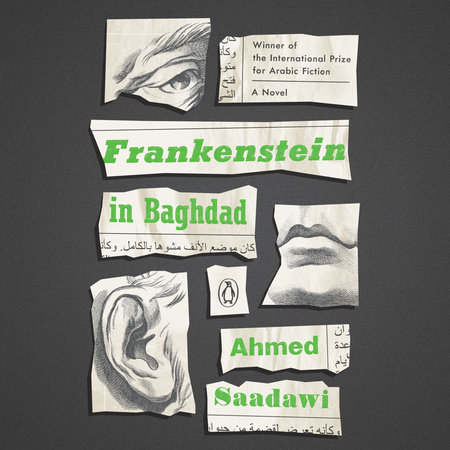

[Frankenstein in Baghdad : A Novel [Ahmed Saadawi

Chapter One : The Madwomen

(1)

THE EXPLOSION TOOK place two minutes after Elishva, the old

.woman known as Umm Daniel, or Daniel’s mother, boarded the bus

Everyone on the bus turned around to see what had happened. They

watched in shock as a ball of smoke rose, dark and black, beyond the

.crowds, from the car park near Tayaran Square in the center of Baghdad

Young people raced to the scene of the explosion, and cars collided into

: each other or into the median. The drivers were frightened and confused

they were assaulted by the sound of car horns and of people screaming

.and shouting

Elishva’s neighbors in Lane 7 said later that she had left the Bataween

district to pray in the Church of Saint Odisho, near the University of

Technology, as she did every Sunday, and that’s why the explosion

,happened—some of the locals believed that, with her spiritual powers

.Elishva prevented bad things from happening when she was among them

Sitting on the bus, minding her own business, as if she were deaf or

not even there, Elishva didn’t hear the massive explosion about two

,hundred yards behind her. Her frail body was curled up by the window

and she looked out without seeing anything, thinking about the bitter

taste in her mouth and the sense of gloom that she had been unable to

.shake off for the past few days

.The bitter taste might disappear after she took Holy Communion

Hearing the voices of her daughters and their children on the phone, she

would have a little respite from her melancholy, and the light would shine

again in her cloudy eyes. Father Josiah would usually wait for his cell

phone to ring and then tell Elishva that Matilda was on the line, or if

Matilda didn’t call on time, Elishva might wait another hour and then ask

the priest to call Matilda. This had been repeated every Sunday for at

least two years. Before that, Elishva’s daughters had called irregularly on

,the land line at church. But then when the Americans invaded Baghdad

their missiles destroyed the telephone exchange, and the phones were cut

off for many months. Death stalked the city like the plague, and Elishva’s

.daughters felt the need to check every week that the old woman was okay

At first, after a few difficult months, they spoke on the Thuraya satellite

phone that a Japanese charity had given to the young Assyrian priest at

the church. When the wireless networks were introduced, Father Josiah

.bought a cell phone, and Elishva spoke to her daughters on that

Members of the congregation would stand in line after Mass to hear the

voices of their sons and daughters dispersed around the world. Often

people from the surrounding Karaj al-Amana neighborhood—Christians

of other denominations and Muslims too—would come to the church to

make free calls to their relatives abroad. As cell phones spread, the

demand for Father Josiah’s phone declined, but Elishva was content to

.maintain the ritual of her Sunday phone call from church

With her veined and wrinkled hand, Elishva would put the Nokia

phone to her ear. Upon hearing her daughters’ voices, the darkness would

lift and she would feel at peace. If she had gone straight back to Tayaran

Square, she would have found that everything was calm, just as she had

left it in the morning. The sidewalks would be clean and the cars that had

caught fire would have been towed away. The dead would have been

.taken to the forensics department and the injured to the Kindi Hospital

There would be some shattered glass here and there, a pole blackened

with smoke, and a hole in the asphalt, though she wouldn’t have been

.able to make out how big it was because of her blurred vision

When the Mass was over she lingered for an extra hour. She sat down

in the hall adjacent to the church, and after the women had set out on

tables the food they brought with them, she went ahead and ate with

everyone, just to have something to do. Father Josiah made a desperate

last attempt to call Matilda, but her phone was out of service. Matilda had

probably lost her phone, or it had been stolen from her on the street or at

some market in Melbourne, where she lived. Maybe she had forgotten to

write down Father Josiah’s number or had some other excuse. The priest

couldn’t make sense of it but kept trying to console Elishva, and when

everyone started leaving, the deacon, Nader Shamouni, offered Elishva a

ride home in his old Volga. This was the second week without a phone

call. Elishva didn’t actually need to hear her daughters’ voices. Maybe it

was just habit or something more important: that with her daughters she

could talk about Daniel. Nobody really listened to her when she spoke

about the son she had lost twenty years ago, except for her daughters and

Saint George the Martyr, whose soul she often prayed for and whom she

saw as her patron saint. You might add her old cat, Nabu, whose hair was

falling out and who slept most of the time. Even the women at church

grew distant when she began to talk about her son—because she just said

the same things over and over. It was the same with the old women who

were her neighbors. Some of them couldn’t remember what Daniel looked

like. Besides, he was just one of many who’d died over the years. Elishva

was gradually losing people who had once supported her strange

conviction that her son was still alive, even though he had a grave with an

.empty coffin in the cemetery of the Assyrian Church of the East

Elishva no longer shared with anyone her belief that Daniel was still

alive. She just waited to hear the voice of Matilda or Hilda because they

would put up with her, however strange this idea of hers. The two

daughters knew their mother clung to the memory of her late son in order

.to go on living. There was no harm in humoring her

Nader Shamouni, the deacon, dropped off Elishva in Lane 7 in

Bataween, just a few steps from her door. The street was quiet. The

slaughter had ended several hours ago, but the destruction was still

.clearly visible. It might have been the neighborhood’s biggest explosion

The old deacon was depressed; he didn’t say a word to Elishva as he

parked his car next to an electricity pole. There was blood and hair on the

pole, mere inches from his nose and his thick white mustache. He felt a

.tremor of fear

Elishva got out of the deacon’s car and waved good-bye. Walking down

the street, she could hear her unhurried footsteps on the gravel. She was

preparing an answer for when she opened the door and Nabu looked up

”?as if to ask, “So? What happened

More important, she was preparing to scold Saint George. The

previous night he had promised that she would either receive some good

news or her mind would be set at rest and her ordeal would come to an

.end

(2)

Elishva’s neighbor Umm Salim believed strongly, unlike many

others, that Elishva had special powers and that God’s hand was on her

shoulder wherever she was. She could cite numerous incidents as

evidence. Although sometimes she might criticize or think ill of the old

woman, she quickly went back to respecting and honoring her. When

Elishva came to visit and they sat with some of their neighbors in the

shade in Umm Salim’s old courtyard, Umm Salim spread out for her a

woven mat, placed cushions to the right and left of her, and poured her

.tea

Sometimes she might exaggerate and say openly in Elishva’s presence

—that if it weren’t for those inhabitants who had baraka—spiritual power

the neighborhood would be doomed and swallowed up by the earth on

God’s orders. But this belief of Umm Salim’s was really like the smoke she

blew from her shisha pipe during those afternoon chats: it came out in

,billows, then coiled into sinuous white clouds that vanished into the air

.never to travel outside the courtyard

,Many thought of Elishva as just a demented old woman with amnesia

the proof being that she couldn’t remember the names of men—even

those she had known for half a century. Sometimes she looked at them in

a daze, as though they had sprung up in the neighborhood out of

.nowhere

Umm Salim and some of the other kindhearted neighbors were

distraught when Elishva started to tell bizarre stories about things that

.had happened to her—stories that no reasonable person would believe

Others scoffed, saying that Umm Salim and the other women were just

sad that one of their number had crossed over to the dark and desolate

shore beyond, meaning the group as a whole was headed in the same

.direction

(3)

Two people were sure Elishva didn’t have special powers or

,anything and was just a crazy old woman. The first was Faraj the realtor

owner of the Rasoul realty office on the main commercial street in

Bataween. The second was Hadi the junk dealer, who lived in a makeshift

.dwelling attached to Elishva’s house

Over the past few years Faraj had tried repeatedly to persuade Elishva

.to sell her old house, but Elishva just flatly refused, without explanation

Faraj couldn’t understand why an old woman like her would want to live

alone in a seven-room house with only a cat. Why, he wondered, didn’t

she sell it and move to a smaller house with more air and light, and use

? the extra money to live the rest of her life in comfort

Faraj never got a good answer. As for Hadi, her neighbor, he was a

scruffy, unfriendly man in his fifties who always smelled of alcohol. He

had asked Elishva to sell him the antiques that filled her house: two large

wall clocks, teak tables of various sizes, carpets and furnishings, and

plaster and ivory statues of the Virgin Mary and the Infant Jesus. There

were more than twenty of these statues, spread around the house, as well

.as many other things that Hadi hadn’t had time to inspect

Of these antiques, some of which dated back to the 1940s, Hadi had

asked Elishva, “Why don’t you sell them, save yourself the trouble of

dusting?” his eyes popping out of his head at the sight of them all. But the

old woman just walked him to the front door and sent him out into the

street, closing the door behind him. That was the only time Hadi had seen

the inside of her house, and the impression it left him with was of a

.strange museum

The two men didn’t abandon their efforts, but because the junk dealer

usually wasn’t presentable, Elishva’s neighbors were not sympathetic to

him. Faraj the realtor tried several times to encourage Elishva’s neighbors

to win her over to his proposal; some even accused Veronica Munib, the

Armenian neighbor, of taking a bribe from Faraj to persuade Elishva to

,move in with Umm Salim and her husband. Faraj never lost hope. Hadi

on the other hand, constantly pestered Elishva until he eventually lost

interest and just threw hostile glances her way whenever she passed him

.on the street

Elishva not only rejected the offers from these two men, she also

reserved a special hatred for them, consigning them to everlasting hell. In

their faces she saw two greedy people with tainted souls, like cheap

.carpets with permanent ink stains

Abu Zaidoun the barber could be added to the list of people Elishva

hated and cursed. Elishva had lost Daniel because of him: he was the

Baathist who had taken her son by the collar and dragged him off into the

.unknown. But Abu Zaidoun had been out of sight for many years

Elishva no longer ran into him, and no one talked about him in front of her. Since

leaving the Baath Party, he had been preoccupied with his many ailments

. and had no time for anything that happened in the neighborhood

(4)

Faraj was at home when the massive explosion went off in

,Tayaran Square. Three hours later, at about ten o’clock in the morning

.he opened his realty office and noticed cracks in the large front window

He cursed his bad luck, though he had noticed the shattered windows of

many other shops in the area. In fact, he could see Abu Anmar, owner of

,the Orouba Hotel across the street, standing bewildered on the sidewalk

in his dishdasha, amid shards of glass from his old hotel’s upper

.windows

Faraj could see that Abu Anmar was shocked, but he didn’t care: he

had no great affection for him. They were polar opposites, even

undeclared rivals. Abu Anmar, like many of the hotel owners in

Bataween, made his living off workers and students and people who came

to Baghdad from the provinces to visit hospitals or clinics or to go

shopping. Over the past decade, with the departure of many of the

Egyptian and Sudanese migrant workers, hotels had become dependent

on a few customers who lived in them almost permanently—drivers on

long-distance bus routes, students who didn’t like the college dorms, and

people who worked in the restaurants in Bab al-Sharqi and Saadoun

Street, in the factories that made shoes and other things, and in the Harj

flea market. But most of these people disappeared after April 2003, and

now many of the hotels were nearly empty. To make matters worse, Faraj

had appeared on the scene, trying to win over customers who might

otherwise have gone to Abu Anmar’s hotel or one of the others in the

.area

Faraj had taken advantage of the chaos and lawlessness in the city to

get his hands on several houses of unknown ownership. He turned these

into cheap boardinghouses, renting the rooms to workers from the

provinces or to families displaced from nearby areas for sectarian reasons

or because of old vendettas that had come back into effect with the fall of

.the regime

Abu Anmar could only grumble and complain. He had moved to

Baghdad from the south in the 1970s and had no relatives or friends in

the capital to help him. In the past he had relied on the power of the

,regime. Faraj, on the other hand, had many relatives and acquaintances

and when the regime fell, they were the means by which he imposed

authority, winning everyone’s respect and legalizing his appropriation of

the abandoned houses, even though everyone knew he didn’t have the

papers to prove he owned them or had ever rented them from the

.government

Faraj could use his growing power against Elishva. He had seen her

house from the inside only twice but had fallen in love with it

immediately. It had probably been built by Jews, since it was in the style

favored by the Iraqi Jews: an inner courtyard surrounded by several

rooms on two floors, with a basement under one of the rooms that

opened onto the street. There were fluted wooden columns supporting

,the arcade on the upper floor. With the metal railings, inlaid with wood

they created a unique aesthetic effect. The house also had double-leaf

wooden doors with metal bolts and locks, and wooden windows

reinforced with metal bars and glazed with stained glass. The courtyard

was paved with fine brickwork and the rooms with small black and white

tiles like a chessboard. The courtyard was open to the sky and had once

,been covered with a white cloth that was removed during the summer

,but the cloth was no longer there. The house was not as it once had been

but it was sturdy and had suffered little water damage, unlike similar

houses on the street. The basement had been filled in at some point, but

that didn’t matter. The main drawback for Faraj was that one of the

rooms on the upper floor had completely collapsed, with many of the

bricks having fallen beyond the wall shared with the house next door; the

total ruin inhabited by Hadi the junk dealer. The bathroom on the upper

floor was also in ruins. Faraj would need to spend some money on repairs

.and renovations, but it would be worth it

Faraj thought it would take only half an hour to evict a defenseless old

Christian woman, but a voice in his head warned him that he risked

breaking the law and offending people, so it might be better to first gauge

people’s feelings about the old woman. The best thing would be to wait

,till she died, and then no one but he would dare to take over the house

since everyone knew how attached he was to it and acknowledged him as

.its future owner, however long Elishva lived

“Look on the bright side,” Faraj shouted to Abu Anmar, who was

wringing his hands in dismay at the damage to his property. Abu Anmar

raised his arms to the heavens in solidarity with Faraj’s optimism, or

maybe he was saying “May God take you” to the greedy realtor whom fate

.had taunted him with all day long

(5)

Elishva shoved her cat off the sofa and brushed away the loose cat

hairs. She couldn’t actually see any hairs, but she knew from stroking the

cat that its hair was falling out all over the place. She could overlook the

hair unless it was in her special spot on the sofa facing the large picture of

Saint George the Martyr that hung between smaller gray pictures of her

son and her husband, framed in carved wood. There were two other

pictures of the same size, one of the Last Supper and the other of Christ

being taken down from the cross, and three miniatures copied from

medieval icons, drawn in thick ink and faded colors, depicting various

saints, some of whose names she didn’t know because it was her husband

who had put them up many years ago. They were still as they were

originally hung, some in the parlor, some in her bedroom, some in

Daniel’s room, which was closed, and some in the other abandoned

.rooms

Almost every evening she sat there to resume her sterile conversation

with the saint with the angelic face. The saint wasn’t in ecclesiastical

dress: he was wearing thick, shiny plates of armor that covered his body

and a plumed helmet, with his wavy blond hair peeking out from under

the helmet. He was holding a long pointed lance and sitting on a

muscular white horse that had reared up to avoid the jaws of a hideous

dragon encroaching from the corner of the picture, intent on swallowing

.the horse, the saint, and all his military accoutrements

Elishva ignored the extravagant details. She put on the thick glasses

that hung from a cord around her neck and looked at the calm, angelic

face that betrayed no emotion. He wasn’t angry or desperate or dreamy or

.happy. He was just doing his job out of devotion to God

Elishva found no comfort in abstract speculation. She treated her

patron saint as one of her relatives, a member of a family that had been

torn apart and dispersed. He was the only person she had left, apart from

Nabu, the cat, and the specter of her son, Daniel, who was bound to

return one day. To others she lived alone, but she believed she lived with

three beings, or three ghosts, with so much power and presence that she

.didn’t feel lonely

She was angry because her patron saint hadn’t fulfilled any of the

three promises she had extracted from him after countless nights of

pleading, begging, and weeping. She didn’t have much time left on this

earth, and she wanted a sign from the Lord about Daniel—whether he

.was alive and would return or where his real grave or his remains were

She wanted to challenge her patron saint on the promises he had given

her, but she waited for night to fall because during the day the picture

was just a picture, inanimate and completely still, but at night a portal

,opened between her world and the other world, and the Lord came down

embodied in the image of the saint, to talk through him to Elishva, the

poor sheep who had been abandoned by the rest of the flock and had

.almost fallen into the abyss of faithless perdition

That night, by the light of the oil lamp, Elishva could see the ripples in

the old picture behind the murky glass, but she could see also the saint’s

eyes and his soft, handsome face. Nabu meowed irritably as he left the

room. The saint’s long arm was still holding the lance, but now his eyes

were on Elishva. “You’re too impatient, Elishva,” he said. “I told you the

Lord will bring you peace of mind or put an end to your torment, or you

will hear news that will bring you joy. But no one can make the Lord act

”.at a certain time

Elishva argued with the saint for half an hour until his beautiful face

reverted to its normal state, his dreamy gaze stiff and immobile, a sign

that he had grown tired of this sterile discussion. Before going to bed, she

said her usual prayers in front of the large wooden cross in her bedroom

.and checked that Nabu was asleep in the corner on a small tiger-skin rug

The next day, after having breakfast and washing the dishes, she was

surprised to hear the annoying roar of American Apache helicopters

flying overhead. She saw her son, Daniel, or imagined she did. There was

Danny, as she had always called him when he was young—at last her

patron saint’s prophecy had come true. She called him, and he came over

”.to her. “Come, my son. Come, Danny

رد مع اقتباس

رد مع اقتباس