غـــــوستاف إيفل

ألكساندر غوستاف إيفل :::

هو مهندس ومعماري فرنسي، ولد في 15 ديسمبر 1832، وتوفي في 27 ديسمبر 1923 عن عمر يناهز 91 عاما. إشتهر بتصميم المنشآت المعدنية - سواء كانت كباري أو سكك حديدية - لكن أشهرها علي الإطلاق كل من تمثال الحرية في نيو يورك وبرج إيفل - الذي حمل عنه اسمه منذ عام 1889 وحتي يومنا هذا.

حـــــياته

ولد غوستاف إيفل في مدينة ديجون شرق فرنسا. وأتم تعليمه وهو في الثالثة والعشرين من عمره بمدرسة الفنون والصناعة ، وذلك في عام 1855، وهو نفس العام التي إستضافت فيه باريس أول معرض دولي علي أرضها.

بدأ إيفل حياته المهنية بالعمل في جنوب غرب فرنسا، حيث أمضي عده سنوات في كمهندس للإشراف علي الأعمال الهندسية لصالح السكك الحديدية الفرنسية، ومن خلال هذه الوظيفة شارك في بناء كوبري السكة الحديدية في بوردو في عام 1864.

تمثال نصفي لغوستاف إيفل علي قاعدة أسمنتية ببرج إيفل

في الفترة بين عامي 1864-1866، شارك إيفل في دراسات عن قناة السويس المصرية. ولاحقا في عام 1866 قام بتأسيس مكتبه الهندسي الخاص، والذي من خلاله بدأ القيام بتنفيذ العديد من المنشآت المعدنية - بخاصة الكباري - في دول مختلفة مثل البرتغال، أسبانيا، رومانيا، وفرنسا.

في عام 1876، ذاع صيته حينما تم اختيار تصميمه الذي تقدم به للمسابقة الدولية لتصميم وبناء كوبري نهر دورو في البرتغال. وقد تم اختيار التصميم لتميزه من ناحية الجمال، ورخص تكلفة إنشاؤه - مقارنة بالتصميمات الآخري التي تقدمت لهذه المسابقة - بالإضافة إلي تطبيقه لنظريات جديدة في الهندسة الإنشائية القائمة علي اكتشافات ماكسويل في 1864. وقد قام بافتتاح هذا الكوبري في 1877 كل من لويس الأول ملك البرتغال وماريا بيا ملكة البرتغال، وقد سمي الكوبري علي اسمها. ظل هذا الكوبري يعمل حتي عام 1991 - أي لمده 114 عام - حيث جري استبداله.

في عام 1900 قام بتصميم مبني لاروش ، وهو مبني دائري مؤلف من ثلاثة طوابق، إنشيء بصورة مؤقته كروتاندا لحفظ الخمر في المعرض الدولي الذي أقيم بباريس عام 1900، وقد أصبح هذا المبني - بدوره - أحد المعالم الأثرية للمدينة اليوم.

آواخـــر حياته

في عام 1889 تعرض إيفل لفضيحة مالية مع فرديناند دى لسبس في مشروع قناة بنما، لكن تم تبرئته لاحقا منها. وعلي آثر هذه الفضيحة، قرر إيفل أن يتفرغ تماما للبحث العلمي، وقد قضي بالفعل الثلاثين عاما الأخيره من عمره يعمل في أبحاث مقاومة المباني للرياح وتصميم نفق الرياح، حتي توفي في منزله بباريس عن 91 عاما حافلة بالعطاء والتميز.

أشــــــهر أعمــــاله

Caricature Gustave Eiffel

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel

Signature

December 1832 – 27 December 1923) was a French civil engineer and architect. A graduate of the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, he made his name with various bridges for the French railway network, most famously the Garabit viaduct. He is best known for the world-famous Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, France. After his retirement from engineering, Eiffel concentrated his energies on research into meteorology and aerodynamics, making important contributions in both fields.

Early life

Gustave Eiffel was born in the department of France, the first child of Alexandre and Catherine Eiffel. The family was descended from Jean-René Bönickhausen, who emigrated from Marmagen and settled in Paris at the beginning of the eighteenth century The family adopted the name Eiffel as a reference to the Eifel mountains in the region from which it had come. Although the family always used the name Eiffel, Gustave's name was registered at birth as Bönickhausen and was not formally changed to Eiffel until 1880.

At the time of Gustave's birth his father, an ex-soldier, was working as an administrator for the French Army but shortly after his birth his mother expanded a charcoal business she had inherited from her parents to include a coal-distribution business and soon afterwards his father gave up his job to assist her. Due to his mother's business commitments, Gustave spent his childhood living with his grandmother, but nevertheless remained close to his mother, who was to remain an influential figure until her death in 1878. The business was successful enough for Catherine Eiffel to sell the business in 1843 and retire on the proceeds Eiffel was not a studious child, and thought his classes at the Lycée Royal in Dijon boring and a waste of time, although in his last two years, influenced by his teachers for history and literature, he began to study seriously, so that he managed to gain his baccalauréats in humanities and science An important part in his education was played by his uncle, Jean-Baptiste Mollerat, who had invented a process for distilling vinegar and had a large chemical works near Dijon, and one of his uncle's friends, the chemist Michel Perret. Both men spent a lot of time with the young Eiffel, teaching him about everything from chemistry and mining to theology and philosophy.

Eiffel went on to attend the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris, in order to prepare for the difficult entrance exams set by the most important engineering colleges in France. Eiffel had hoped to enter the École Polytechnique, but his tutors decided that his performance was not good enough, and instead he qualified for entry to the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris, which offered a rather more vocational training During his second year he chose to specialize in chemistry, and graduated 13th of the 80 candidates in 1855. This was the year that Paris hosted the first World's Fair, and Eiffel was bought a season ticket by his mother

In 1886 Eiffel also designed the dome for the Astronomical Observatory in Nice. This was the most important building in a complex designed by Charles Garnier, later among the most prominent critics of the Tower. The dome, with a diameter of 22.4 metres (73 ft) was the largest in the world when built and used an ingenious bearing device: rather than running on wheels or rollers, it was supported by a ring-shaped hollow girder floating in a circular trough containing a solution of magnesium chloride in water. This had been patented by Eiffel in 1881.

The Eiffel Tower

Main article: Eiffel Tower

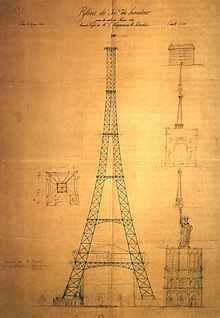

Koechlin's first drawing for the Eiffel Tower. Note the sketched stack of buildings, with Notre Dame at the bottom, indicating the scale of the proposed tower.

The design of the Eiffel Tower was originated by Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, who had discussed ideas for a centrepiece for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. In May 1884 Koechlin, working at his home, made an outline drawing of their scheme, described by him as "a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals Initially Eiffel showed little enthusiasm, although he did sanction further study of the project, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre to add architectural embellishments. Sauvestre added the decorative arches to the base, a glass pavilion to the first level and the cupola at the top. The enhanced idea gained Eiffel's support for the project, and he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier and Sauvestre had taken out. The design was exhibited at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884, and on 30 March 1885 Eiffel read a paper on the project to the Société des Ingiénieurs Civils. After discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying that the tower would symbolise

"not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France's gratitude."

Little happened until the beginning of 1886, but with the re-election of Jules Grévy as President and his appointment of Edouard Lockroy as Minister for Trade decisions began to be made. A budget for the Exposition was passed and on 1 May Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition which was being held for a centerpiece for the exposition, which effectively made the choice of Eiffel's design a foregone conclusion: all entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars. On 12 May a commission was set up to examine Eiffel's scheme and its rivals and on 12 June it presented its decision, which was that only Eiffel's proposal met their requirements. After some debate about the exact site for the tower, a contract was signed on 8 January 1887. This was signed by Eiffel acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, and granted him one and a half million francs toward the construction costs. This was less than a quarter of the estimated cost of six and a half million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation during the exhibition and for the following twenty years Eiffel later established a separate company to manage the tower.

The tower had been a subject of some controversy, attracting criticism both from those who did not believe it feasible and from those who objected on artistic grounds. Just as work began at the Champ de Mars, the "Committee of Three Hundred" (one member for each metre of the tower's height) was formed, led by Charles Garnier and including some of the most important figures of the French arts establishment, including Adolphe Bouguereau, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod and Jules Massenet: a petition was sent to Charles Alphand, the Minister of Works, and was published by Le Temps

"To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour de Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years ... we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal"

18 July 1887

7 December 1887

20 March 1888

15 May 1888

21 August 1888

26 December 1888

March 1889

Work on the foundations started on 28 January 1887. Those for the east and south legs were straightforward, each leg resting on four 2 m (6.6 ft) concrete slabs, one for each of the principal girders of each leg but the other two, being closer to the river Seine were more complicated: each slab needed two piles installed by using compressed-air caissons 15 m (49 ft) long and m (20 ft) in diameter driven to a depth of 22 m (72 ft) to support the concrete slabs, which were 6 m (20 ft) thick. Each of these slabs supported a limestone block, each with an inclined top to bear the supporting shoe for the ironwork. These shoes were anchored by bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long. Work on the foundations was complete by 30 June and the erection of the iron work was started. Although no more than 250 men were employed on the site, a prodigious amount of exacting preparatory work was entailed: the drawing office produced 1,700 general drawings and 3,629 detail drawings of the 18,038 different parts needed.

The task of drawing the components were complicated by the complex angles involved in the design and the degree of precision required: the position of rivet holes were specified to within 0.1 mm (0.04 in) and angles worked out to one second of arc. The components, some already riveted together into sub-assemblies, were first bolted together, the bolts being replaced by rivets as construction progressed. No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit it was sent back to the factory for alteration. The four legs, each at an angle of 54° to the ground, were initially constructed as cantilevers, relying on the anchoring bolts in the masonry foundation blocks. Eiffel had calculated that this would be satisfactory until they approached halfway to the first level: accordingly work was stopped for the purpose of erecting a wooden supporting scaffold. This gave ammunition to his critics, and lurid headlines including "Eiffel Suicide!" and "Gustave Eiffel has gone mad: he has been confined in an Asylum" appeared in the popular press

At this stage a small "creeper" crane was installed in each leg, designed to move up the tower as construction progressed and making use of the guides for the elevators which were to be fitted in each leg. After this brief pause erection of the metalwork continued, and the critical operation of linking the four legs was successfully completed by March 1888. In order to precisely align the legs so that the connecting girders could be put into place, a provision had been made to enable precise adjustments by placing hydraulic jacks in the footings for each of the girders making up the legs.

By June construction had reached the second level platform, and on Bastille Day this was used for a fireworks display, and Eiffel held a celebratory banquet for the press on the first level platform.

The main structural work was completed at the end of March, and on the 31st Eiffel celebrated this by leading a group of government officials, accompanied by representatives of the press, to the top of the tower . Since the lifts were not yet in operation, the ascent was made by foot, and took over an hour, Eiffel frequently stopping to make explanations of various features. Most of the party chose to stop at the lower levels, but a few, including Nouguier, Compagnon, the President of the City Council and reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré completed the climb. At 2.35 Eiffel hoisted a large tricoleur, to the accompaniment of a 25-gun salute fired from the lower level

Illustration of Eiffel's lock design from a contemporary magazine

In 1887, Eiffel became involved with the French effort to construct a canal across the Panama Isthmus. The French Panama Canal Company, headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps, had been attempting to build a sea-level canal, but came to the realization that this was impractical. The plan was changed to one using locks, which Eiffel was contracted to design and build. The locks were on a large scale, most having a change of level of 11 m

(36 ft).

Eiffel had been working on the project for little more than a year when the company suspended payments of interest on 14 December 1888, and shortly afterwards was put into liquidation. Eiffel's reputation was badly damaged when he was implicated in the financial and political scandal which followed. Although he was simply a contractor, he was charged along with the directors of the project with raising money under false pretenses and misappropriation of funds. On 9 Feb 1893 Eiffel was found guilty on the charge of misuse of funds, and was fined 20,000 francs and sentenced to two years in prison although he was acquitted on appeal The later American-built canal used new lock designs (see History of the Panama Canal).

Shortly before the trial Eiffel had announced his intention to resign from the Board of Directors of the Compagnie des Establissments Eiffel, and did so at a General Meeting held on 14 February, saying "I have absolutely decided to abstain from any participation in any manufacturing business from now on, and so that no one can be misled and to make it most evident that I intend to remain absolutely uninvolved with the management of the establishments which bear my name, I wish to that my name should disappear from the name of the company The company changed its name to La Société Constructions Levallois-Perret, with Maurice Koechlin as managing director. The name was changed to the Anciens Establissments Eiffel in 1937

After his retirement from the Compagnie des Establissments Eiffel, Eiffel went on to do important work in meteorology and aerodynamics

Eiffels's interest in these areas was a consequence of the problems he had encountered with the effects of wind forces on the structures he had built.

His first aerodynamic experiments, an investigation of the air resistance of surfaces, was carried out by dropping the surface to be investigated together with a measuring apparatus down a vertical cable stretched between the second level of the Eiffel Tower and the ground. Using this Eiffel definitely established that the air resistance of a body was very closely related to the square of the airspeed. He then built a laboratory on the Champ de Mars at the foot of the tower in 1905, building his first wind tunnel there in 1909. The wind tunnel was used to investigate the characteristics of the airfoil sections used by the early pioneers of aviation such as the Wright Brothers, Gabriel Voisin and Louis Blériot. Eiffel established that the lift produced by an airfoil was the result of a reduction of air pressure above the wing rather than an increase of pressure acting on the under surface. Following complaints about noise from people living nearby, he moved his experiments to a new establishment at Auteuil in 1912. Here it was possible to build a larger wind tunnel, and Eiffel began to make tests using scale models of aircraft designs.

In 1913 Eiffel was awarded the Samuel P. Langley Medal for Aerodromics by the Smithsonian Institute. In his speech at the presentation of the medal, Alexander Graham Bell said

...his writings upon the resistance of the air have already become classical. His researches, published in 1907 and 1911, on the resistance of the air in connection with aviation, are especially valuable. They have given engineers the data for designing and constructing flying machines upon sound, scientific principles

Eiffel had meteorological measuring equipment placed on the tower in 1889, and also built a weather station at his house in Sèvres. Between 1892 and 1891 he compiled a complete set of meteorological readings, and later extended his record-taking to include measurements from 25 different locations across France.

Eiffel died on 27 December 1923, while listening to Beethoven's 5th symphony andante, in his mansion on Rue Rabelais in Paris, France. He was buried in the Cimetière de Levallois-Perret.

Edward Moran's 1886 painting, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, depicts the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty.

Edward Moran's 1886 painting, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, depicts the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty.

Gustave Eiffel's career was a result of Industrial Revolution. For a variety of economic and political reasons, this had been slow to make an impact in France, and Eiffel had the good fortune to be working at a time of rapid industrial development in France. Eiffel's importance as an engineer was twofold. Firstly he was ready to adopt innovative techniques first used by others, such as his use of compressed-air caissons and hollow cast-iron piers, and secondly he was a pioneer in his insistence on basing all engineering decisions on a base of thorough calculation of the forces involved, combining this analytical approach with an insistence on a high standard of accuracy in drawing and manufacture.

The growth of the railway network had an immense effect on people's lives, but although the enormous number of bridges and other work undertaken by Eiffel were an important part of this, the two works that did most to make him famous are the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower, both projects of immense symbolic importance and today internationally recognized landmarks. The Tower is also important because of its role in establishing the aesthetic potential of structures whose appearance is largely dictated by practical considerations.

His contribution to the science of aerodynamics is probably of equal importance to his work as an engineer

اتمنى الموضوع يكون نال على رضاكم

كل احتــــرامي لكم

Edward Moran's 1886 painting, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, depicts the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty.

Caricature Gustave Eiffel

Caricature Gustave Eiffel

رد مع اقتباس

رد مع اقتباس